Sanatçı Röportajı: Pat Hickman

You did your MA in Design/Textiles from the University of California, Berkeley. Looking at the beginning of your career as an artist, how did you get started on your artistic journey, working in textiles as a medium?

My grandmother made quilts, always flower garden patterns. Even when she could no longer organize quilt blocks, she loved moving printed cloth patterns and colors around, putting them together. She had such a good eye and passion for what she did. She was unknowingly an influence on me.

But it was while living and teaching English language and literature in Turkey, exploring in Istanbul and in the countryside, that I discovered Turkish art and architecture, including beautiful, handcrafted textiles. I wanted to learn about them and so began my study of textile processes. I eventually attended a class at the Applied Fine Arts Academy in Istanbul and began to learn to weave.

Above: Pat Hickman, Still Counting, photographed by George Potanovic, Jr.

When did you start experimenting with textiles?

I felt very lucky to be in graduate school at the University of California Berkeley during the 70s. Since I hadn’t studied art as an undergraduate, I lingered longer than was usual in the Textile Design program, completing a written thesis on Turkish “oya,” needle lace edging. I had returned for a research year to Istanbul to study what I had observed earlier, how women communicated visual messages with tiny three-dimensional edging on their headscarves. For example, if a woman was arguing with her husband, I understood she wore a scarf with red pepper edging and nothing needed to be said. Or she could announce her pregnancy with small stuffed pink forms, or inform her community that her son had gone to the army. I found this silent communication of great interest. Such wordless communication is what art does. I knew I wanted to be part of this world of visual communication through my studio making.

What aspect of textiles do you think makes a difference in terms of visual communication?

I come out of a textile tradition and respond to the expressiveness of cloth, of fibrous materials, of flexible linear materials, of making something out of seemingly nothing, of forgiving materials. I use natural materials—reeds and branches, found materials, rusted materials, paper—that which speaks of time and memory, of materials which feel close to life. I create structure out of stiff materials which I can manipulate, sometimes covering structures with skin membrane. I find materials which express what I’m trying to say in my artwork.

They are familiar and accessible. At this point in time when divisions between media are breaking down, painters and sculptors are choosing to use fiber, combining it with their materials. They do not come out of a textile background, knowing the traditional techniques used historically in world textiles, but, I believe, they are responding to the expressive quality of those materials.

Does your personal life play a role in your art practice?

I grew up in a small town in northeastern Colorado, on the prairie. My mother was a grade school teacher; my dad was a butcher who co-owned a small grocery store. I had trouble watching him occasionally butcher at his sister’s ranch. People in my family hunt and fish, eating the meat they get. I liked going with Dad to find arrowheads or to discover “treasures” in a dump. Dad had a curiosity, which I think I inherited, about the larger world. He loved National Geographic Magazine.

I work with materials found in the natural world, a practice begun decades ago in Alaska, where I had the opportunity to research the use of gut and fish skin materials. There, I witnessed how indigenous people used seal and walrus intestines to create waterproof parkas, transforming an inner membrane into an outer protective garment. With deep respect for what I learned, I began to use similar thin membranes which became my signature material. I use gut as both skin and structure, giving this hidden material new life.

For 21 years, I lived on the Plains of Colorado - flat, hard, dust-blown. The endless expanse where I grew up held little beauty for me.

In my piece “Tumbleweed,” made with knotted-netting, I express yearning, knowing I was shaped by that place where I started, even as I had to leave it. I was late in discovering that there was such a thing as art. In high school, the art teacher was a coach and driver’s education teacher, not someone who opened us to the world of art. Going to art museums was not part of my growing up.

After spending two years in Turkey, I returned to the United States, to the Boston area, and began to take textile art classes at the Cambridge Adult Education Center, studying with Joanne Segal Brandford. This was in the early the 1970s, when there was great excitement about art in the fiber medium. The mood at that time in the fiber world was that everything began in the 1970s. From my appreciation of traditional Turkish textiles I knew otherwise. By then, I had a deep interest in ethnographic world textiles, in textile history, and wanted to learn more. Joanne encouraged my pursuit of that direction, along with learning through my hands as a maker. When my family (my husband and twin daughters) and I were leaving the east coast for Berkeley, Joanne encouraged me to study with Lillian Elliott and with Ed Rossbach once I was in California, knowing that they could become very significant mentors for me.

You use weaving in some of your works in various of ways. What's the role of weaving in your work?

Loom weaving was one of many techniques I studied as part of textile history and learning about textiles from around the world. I responded to the sophisticated knowledge of others before me—makers who had manipulated fibers in both two and three dimensional ways to create that which gave meaning to their lives.

Is there any recurring theme/question in your practice?

Using perishable materials to make visual metaphors, I address ongoing themes of impermanence and mortality, the desire to hold on to life yet a bit longer.

In your practice, you experiment with natural materials in a variety of ways. It varies from gut and skin-like materials, sausage casings, fiber, metals and nets. How did you get into using fiber in your works?

My route to becoming an artist was, and still is, greatly informed by place—by where I live. The 1970s were such a heady time in Berkeley, which (we were convinced) was the center of the Fiber movement. Many well trained fiber artists, who’d come out of programs at California College of Arts (& Crafts) and/or the University of California at Berkeley, wanted to linger there, teaching part time in whatever classes they could offer at local textile art schools. Artists from elsewhere came to these institutions to be part of the scene. I went to every possible lecture and museum exhibit in the Bay Area, which was hopping with visiting artists passing through, offering workshops—a most frenetic, exciting time. Those of us who lived there and were part of this time benefitted from it all.

When I completed my degree, Ed Rossbach was going on sabbatical and asked me to teach a textile history course for one semester. He recognized my deep interest in the subject. He trusted that I would rise to this challenge long before I had recognized I could move in this direction. Teaching his course helped shape what I subsequently wanted to offer in my own teaching, along with studio courses.

One of the areas I included in my textile history course of the Americas and Europe focused on the textiles of Alaska. I’d seen a gut parka on display in an exhibit on Ethnic Textiles at the downtown center of the de Young Museum in San Francisco. In preparation for teaching the textile history course, I carefully studied and photographed many gut and fish skin parkas from Alaska in the Lowie Museum of Anthropology (now the Phoebe Hearst) collection, and felt the need for my own hands to experiment with a related material. So from a delicatessen in Oakland, I purchased sausage casings (as inner skin membrane) and began my exploration.

You also use animal membrane in your works. Can you tell us more about this concept?

There was no “how to” reference for artists working with animal membrane. My process has been one of research and exploration, an intuitive process of experimenting, creating a tough membrane, almost like parchment, through the building up of layers. I work with wet sausage casings. When they dry, stretched over a structure, they become taut. I’m interested in both structure and skin. The contraction of gut when drying, the pulling power of those membranes, changes the shape of a structure, finally achieving a balance, a resolution of the separate materials.

Do you collect any objects as an artist?

I don’t think of myself as a collector, though when possible I have purchased ethnographic textiles for myself and to share with students as an idea rich study collection. I have photographed textiles (and many other things) as an idea file, for the same reasons.

Looking at your installation works, what ideas are you aiming to explore? Does the exhibition space define how the installation is formed?

Yes, the exhibition space totally determines the installation work what the shape of that work will become as in “Permeable”. Fishermen know nets—making, mending, using them to catch, to hold, to carry. I created this suspended net, a delicate mesh, to hold air and light—most of all celebrating that it’s open and porous—not to trap or keep out but permeable, for passing through.

Labor is a big part of my work, the excessive, obsessive labor, the slowing down of time, stepping out of the urgent pace of daily life. Out of seemingly nothing, something is created. I invest in what I love doing. In the end the work itself is about the labor and about holding what cannot be captured: light, color, breath, time.

Place, where I’m living and working, makes a huge difference in my work. That can happen as well on artist residencies.

I respond to place through the materials available to me as potential art materials, materials that to me carry meaning and ideas. When living in Hawaii, the materials around me - palm sheaths and other natural plant materials I could transform - influenced me.

Where I live and work now in New York, I’m responding to the marks made by rust.

In a brick complex near my studio in Garnerville, NY, I covered a rusty elevator door, approximately 170 years old, with gut. Workers, in this series of buildings beginning in the 1830s, dyed and printed calico cloth. The elevator door speaks of time and change. Some of the metal has disappeared exposing the weathered wooden frame beneath. I have picked up the patterning from the rust, transferred it onto the gut skin membrane, responding to the history of this place. I like the intimacy of this material - one thing becoming another through touch and the passage of time. Most recently, after the devastation of a hurricane on this complex, with debris pouring through the creek and destroying the gallery, the heart of this place, I’ve partially covered this door, “Calicoed by Rust,” with what appear to be tossed metal railroad plates, (simulated in gut) creating “Downriver Ravages.” There is the passage of a freight train very near where I live, thus residue of discarded train tracks seem part of this time and place.

My installations with river teeth evoke both memory and constant change.

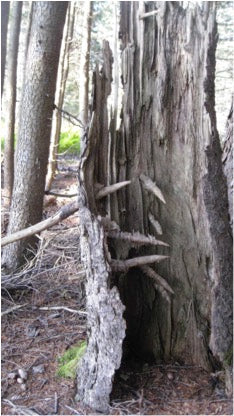

A tree falls. Over time, living creatures, wind and weather hollow it from the inside out, exposing what before was invisible: the cross-grained, pitch-hardened remains of branches that grew from the interior out through the bark to become a branch. We call them knots when they appear sliced in a cut board. Found in rivers and worn smooth, sailors called them river teeth. (See image below).

I cover these objects with skin membrane, the inner guts of an animal. What is invisible in the body becomes an outer skin, covering what was invisible in the tree.

In "Traces of Time", You use visual metaphors such as ‘river teeth’ and ‘rust’. Can you talk a bit about the making of works in "Traces of Time"? How do you approach the concept of time in this series?

In life, I'm aware that “everything changes”. That seems to me the one constant we can count on. My work addresses that, as I often address issues of mortality in my work.

This piece, “Ripples”(see image below), with stitching around bodies of dehydrated geckoes sandwiched between layers of skin membrane, speaks of time, of both life and death.

What constitutes your perception of home? Which cities have you lived in before and how did they shape your practice?

For me, home is (though it sounds like a cliche) where the heart is, where one feels safe, where one can be oneself—free to create and feel supported in one’s work, in one’s imagination. Free to explore and experiment, to thrive and admit failure, to be honest with oneself. To feel loved.

Some of the places that inspire me are: Berkeley in the San Francisco Bay Area was a place where I have felt very much at home, where I grew into being an artist with support for what I was studying and learning in that environment which fed my interest in art and culture. And now, I live near New York City in Haverstraw, on the Hudson River. Wanting to live by water was encouraged by my experience of living in Istanbul on the Bosphorus. Proximity to museums and galleries in NYC has been very important for me in this phase of my life, enriched by going regularly to see exhibits and the work of other artists. Honolulu, Hawaii was home for me, where I lived and taught at the University for sixteen years. There I learned a lot from others, from students and colleagues, being closer to Asia, but on an island in the middle of the Pacific. I was moved especially by the beauty and volcanic energy evident on the Big Island of Hawaii. The beauty and rawness of the Northern CA coast, the Maine woods and cities and museums almost everywhere have influenced me.

How do you connect with nature in your work?

At home, I’m inspired by what is outside my windows, where I see the Hudson river daily and its movement.

In this work, "The River That Flows Both Ways", with credit to the Native American name for the Hudson, Mahicantuck, I used river teeth in a new way for me, drawing with them—with their shape to capture movement and flow. I went with what nature was giving me in those found wooden forms, rather than imposing a configuration that they fit into.

Is there any memorable project/exhibition(s), trip or art residency that you regard as a milestone in you artistic journey?

Living in Istanbul for seven years, spread over many separate visits had a huge impact on my artistic vision and journey. Artist residencies in Maine, both at Haystack and Monson Arts have provided me uninterrupted time to focus on my studio art, encouraging significant changes in my practice.

What and who inspires you as an artist?

I think of “seen and unseen” natural forces that shape my work, about “lifeforce” and the miracle of human bodies working mostly as well as they do. When I first saw a gut parka from Alaska, made of seal or walrus intestine, I found the idea of the translucent membrane beautiful, transformed into a wearable, protective outer waterproof garment. I became interested in that which is unseen, in the interior of a body, that it can become seen, given new life. I wanted to experiment with skin membrane that might be accessible to me. I started exploring what I might do with sausage casings which I now get from www.sausagemaker.com. A lot of my work addresses the fragility of life, bringing ideas of life and death together with the use of this skin membrane. In covering river teeth with skin membrane, I take that which is inside a tree, invisible from the outside—the river tooth which is holding a branch to the tree trunk—and make it visible, combining the unseen from the plant world with the unseen from the animal world, bringing them together, making both visible.

Having lived and taught in Hawaii, I remain awed by the force of the volcano on the Big Island and massive flowing lava, resulting in incredible formations in black lava fields. I’m moved by that unseen power and energy when it’s made visible, sometimes in horrific, destructive ways. I have not found ways to have this shape my work, as it seems impossible to imitate or duplicate the beauty and power of nature, though designing the monumental entrance gates for the Maui Arts & Cultural Center (1991-1994) and working

with the foundry at the University of Tasmania, is the closest I’ve come to fire and molten metal in casting.

I’m inspired by the work of Ann Hamilton, Doris Salcedo, Kimsooja, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Sonya Clark, Joyce Scott, Jim Bassler, etc. The list could go on much longer.

Alongside your career as an artist, you’ve been teaching in Textile and Fiber programs for more than 20 years. What did you enjoy about it the most?

I most enjoyed the interaction and connection with others, seeing what can happen in an encouraging, creative space of learning. I still occasionally teach short term workshops.

In Hawaii, from native Hawaiian students and others, especially from the Pacific Islands, I came to understand a deep connection to the living earth, and all that is in it—knowledge that has been understood by indigenous peoples from the beginning—but I had not experienced it or taken it in, as much as I did the years I lived and taught at the University of Hawaii. I became much more aware of non Western ways of thinking, realizing how my own perspective was from a Western point of view, from Western based education central to my view of the world. I learned a lot by living there.

Are there any books that change the way you look at art?

"Ed Rossbach: Forty Years of Exploration and Innovation in Fiber Art" by Rebecca Stevens, “The New Basketry”, "Baskets as Textile Art” and “The Art of Paisley” by Ed Rossbach, “Daybook: The Journal of an Artist” and “Turn” by Anne Truitt, “Ways of Seeing” by John Berger and “Ann Hamilton” by Joan Simon.

Can you tell us about the works; "Count", "Silent", "Still Counting" and "Letter Home"? How are they related to time and counting? What are they made of?

“Count”, “Silent”, and “Letter Home” are made with found rusty nails sandwiched between layers of skin membrane. That universal symbol of counting, hash or tally marks, marking time, is familiar around the world, with slight variation. One, two, three, four, and five—with five (usually) as a diagonal across the four vertical lines. Sometimes we associate them with incarcerated prisoners and marks on a wall, counting days imprisoned. I’ve presented these in different configurations. Rust speaks of past age and time. These works are about communication and counting time, leaving the viewer the chance to imagine what is implied if they appear as a paragraph, or in the formation of a letter home--what might be said or wish one had said. “Still Counting” was created after a time of police brutality and the killing of another black man in the US. It was made with thin black pins, usually used for mounting insects or a few black nails—again sandwiched between layers of skin membrane. It was created out of an urgent plea to confront the systemic racism in my country.

Lastly, how have you been spending your time for the last three months during self-quarantine?

"Extracted from "Interview with Pat Hickman" by Karl Reichert and Gail Hovey, Copyright Textile Center, reproduced by kind permission.”

Last summer, horrified by the news from the U.S.-Mexican border about walls and children being separated from their families, Pat Hickman began to do what artists do when they are troubled. She turned to her work, beginning to net, not knowing where the project would go or even what it would mean. Her material was metaphorical: a functional fishnet intended to gather food transformed into a barbed wire fence intended to keep things out. Pat worked with strips of old Japanese fishing nets, which she had purchased from habutextiles.com. When the fishing nets were cut apart, what remained were long lines of thread, short pieces sticking out from each knot, like the barbs on barbed wire. Pat began to net these strands into new nets.

Pat was in Washington State in early March, teaching a workshop, when news of the coronavirus first came to our attention. Meeting with a Japanese-American friend and colleague, Jan Hopkins, they spoke of the Internment Camps during World War II. Jan had recently exhibited her Japanese Internment Art series, based on her own family members’ experiences before, during and after the mass incarceration. Returning home, Pat began to read poetry from the camps.

Suddenly her nets became more urgent to make and took on more complicated meanings. What started out as a cry against trying to keep people out became a statement of the futility of trying to keep a virus out. “These things are driving my work,” Pat said. “I have to respond to this horrible moment we are all now experiencing.”

In addition to re-netting the few balls she has of Japanese fishing nets, Pat is cutting up black plastic deer fence nets, lines left on either side of a knot, simulating barbs. “When I cut these nets apart, they too, look like barbed wire.”

Pat spent time near Seattle, an early hotspot of the pandemic. Coming home she read Poets Behind Barbed Wire, an anthology of poems written by people of Japanese ancestry, 70,000 of them American-born citizens. Being forced to shelter in place, listening to COVID-19 being called the “Chinese virus” and watching Chinese Americans being attacked and stigmatized – all these things are spilling into Pat’s work. When she began, Pat called this piece “Wall.” By the time she finishes, it will need a new name.

This is a work still in progress, which has grown to be a larger installation, and will continue to build during the pandemic.

Above: Pat Hickman, Gone, from the exhibition "Traces of Time”

Pat Hickman, Gallipoli Revisited from the exhibition "Traces of Time”

Pat Hickman, Silent, photographed by Neil Alexander

Pat Hickman, Wall, work in progress.